Feb 15, 2017 • 5 min read

Coaching the Squat for Long-Term Success

Teaching young athletes basic strength-building moves is one of the most important things we do as coaches. In my last post, I discussed how a simple tweak in push-up form can make a big difference for long-term development. In this post, I’d like to cover an exercise that is often neglected at youth practices: The squat.

The squat is everywhere in sports. Whether it’s jumping for a layup or breaking down to field a grounder, athletes are constantly moving in and out of the squat position. Regardless of the sport, it’s critical to teach young kids how to squat properly.

Squatting can help athletes jump higher, run faster and even avoid lower-body injuries. Furthermore, squats can be an excellent fitness tool young athletes can come back to after they are no longer in competitive sports.

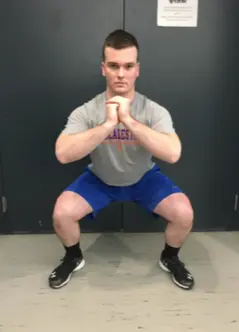

However, it is essential that young athletes have solid bodyweight squat mechanics to serve as a foundation from which to build upon. With that being said, squatting is highly individual and can look vastly different from person to person. Because of this, I focus on teaching athletes to avoid two common pitfalls when squatting.

Pitfall #1: The first common flaw in squat form is caving the knees inward. This happens quite often to athletes when they are first learning the movement. Squatting like this can place stress on the knee and could lead to injuries down the road.

When performed properly, the knees should track directly over the toes as the athlete descends into the squat. While coaches often use the cue “knees out,” I prefer to tell the athlete to focus on keeping their knees in line with their toes. This helps avoid awkward positions that place the knees well outside of the feet, which can be equally dangerous.

Pitfall #2: Another common flaw in squat form occurs when the heels come off the ground. As athletes try to get depth in their squat, they will usually resort to lifting their heels off the ground to make the movement easier.

While it may seem a little unnatural at first, good squat mechanics necessitate that athletes sit back on their heels and feel their bottom track backwards in order to reach the bottom of their squat. When teaching beginners this movement, I recommend using bleachers, chairs or any other knee-height objects they can sit on.

To perform a bleacher squat, stand 1-2 feet away from the object and try to touch it with your bottom. The key here is touch. Sitting on the object will allow the body to relax in the position, but you want to keep the tension. This way, when you take the object away, your body will be ready to do a full squat.

If the implement at knee height is too difficult, try adjusting the height upward and gradually progressing downward until the athlete can properly use the implement at knee height. Once an athlete can properly perform 10 bleacher squats, they should be capable of doing a regular bodyweight squat.

After your players have their squat mechanics down, start to use them as a regular part of conditioning at practice. For example, divide your team into three stations. Station one is a push-up contest. See who can do the most push-ups and only count good ones (V-shape push-ups only!). Station two is a squat contest. Again, only count good ones. The third station is a running station. Cycle through each station twice, and your conditioning session will tackle not only cardiovascular fitness, but also help reinforce solid pushup and squat mechanics. Your kids will also love the competitive aspect of the stations and come to dread the conditioning part of practice a little less.

Quentin Stuart is a senior economics major at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota. He is passionate about youth athletic development and has worked at gyms across the country where he has trained youth, college, and professional athletes. You can contact Quentin at qstuart@macalester.edu.