Just One Season Of Contact Sports Can Hurt A Young Athlete’s Brain

By Dan Peterson, TeamSnap’s Sports Science Expert

Despite the common sense logic that discourages young athletes from smacking their heads together, the medical community continues to confuse the issue with conflicting research reports. Two recent studies report that measurable changes occur in the brains of young football players after just one year on the field while another paper concluded that there were no significant changes in long-term cognitive function for youth players with years of experience, including those that had suffered concussions.

First, the bad news. At this month’s 2nd Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS), Wake Forest University Medical School neurology researchers presented their findings that a single season of high school football head contact can change a player’s brain.

During the 2012 season, they outfitted 45 high school players with helmets that included the Head Impact Telemetry System (HITS) to detect the intensity of impacts during a game. Players also received a pre-season and post-season MRI of their head. Combining data from the HITS along with observing the two MRI image studies, the researchers concluded that one season of play physically changed the players’ brains, even if they did not suffer a concussion during the season.

In a similar study published in the January issue of Neurology, Dr. Thomas McAllister of Indiana University tracked 80 college athletes in contact sports (football and hockey) and 79 non-contact athletes (track, crew, and Nordic skiing) throughout a season. All were given pre and post season MRI head scans and the contact sport athletes wore accelerometers in their helmets to detect collision forces. They were also given tests of verbal learning and memory before and after the season.

The MRI scans again showed a significant difference in brain structure, this time in its “white matter”, consisting of mostly axon fibers, between the contact and non-contact athletes.

"The contact sports and noncontact-sports groups differed, and the number of times the contact sports participants were hit, and the magnitude of the hits they sustained, were correlated with changes in the white matter measures," said Dr. McAllister, chair of the IU Department of Psychiatry. "In addition, there was a group of contact sports athletes who didn't do as well as predicted on tests of learning and memory at the end of the season, and we found that the amount of change in the white matter measures was greater in this group.”

So, both the Wake Forest and IU neurologists warn against the dangers of repeated blows to the skull, showing that just one season can make a difference.

"This study raises the question of whether we should look not only at concussions but also the number of times athletes receive blows to the head and the magnitude of those blows, whether or not they are diagnosed with a concussion," Dr. McAllister said.

Still, Dr. Gregory Stewart, Associate Professor of Orthopaedics at Tulane University and team physician for the university’s athletic department, does not agree. At last month’s Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) in New Orleans, he presented research that showed no connection between years of youth football and neurocognitive function.

By reviewing data from 1,289 New Orleans high school football players between 1998 and 2001, he found no decrease in performance on cognitive tests including the digit symbol substitutions (DSS), pure reaction time (PRT) and choice reaction time (CRT). In fact, as players got older, they did even better on the tests, including the 4% of players who suffered a concussion during the time period.

"The correlation between the number of years of football participation and the performance on the digit symbol substitution test does not support the hypothesis that participation in a collision sport negatively affects neurocognitive function," Dr Stewart said. "The implication is that the playing of football is not in and of itself detrimental."

The NFL, who are in the middle of a legal and PR battle regarding head injuries of professional players, were quick to mention the study on their website.

All of these researchers regard concussions as serious and recommend proper precautionary instruction and equipment and complete follow-up with a physician after any head injury.

The bottom line is still common sense. Parents make the final decision of which sports their kids can play and the ongoing risk factors to their long-term health.

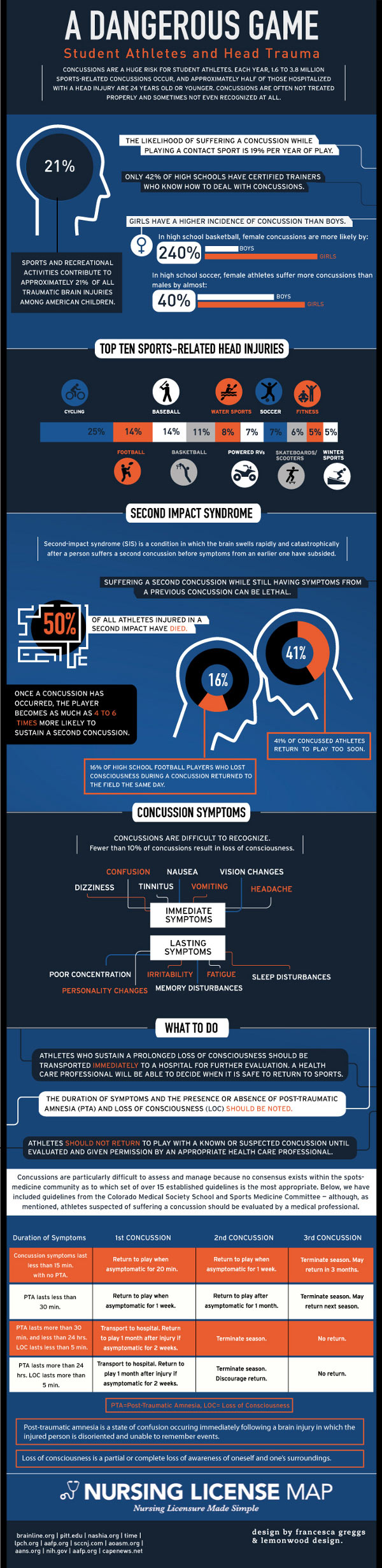

Infograph Source: nursinglicensemap.com/head-trauma

NEW! Free Sports Organization Resources

All of TeamSnap's ebooks, articles, and stories in one place. Access Now

Similar Articles:

HITS Helps Researchers Understand Concussions

By Dan Peterson, TeamSnap's Sports Science Expert Attacking…

Read More

The 5 Most Common Causes of Injury to Kids

By Dan Peterson, TeamSnap's Sports Science Expert …

Read More

Just One Season Of Contact Sports Can Hurt A Young Athlete’s Brain

By Dan Peterson, TeamSnap’s Sports Science Expert…

Read More